As the world enters into the 20th month of Covid eruption period, the jostle for global leadership between US and China had shifted from trade war towards a new frontier of vaccine policy.

While the dust has yet to settle on the prevailing party, China has within a year rewritten the Covid narratives casting global influences turning its valley point of a pandemic outbreak which was almost named after the originating Chinese city, Wuhan, to a leading country which exported most vaccines to save lives at various developing economies.

At the first half of 2021, US rebuilds trans-atlantic ties, placing more weight to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with Australia, India and Japan, as well as, G7. China focuses on international diplomacy across Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia.

Notably South East Asia is a critical maritime channel for global trade and the region emerges as US top investment in Asia. Correspondingly, ASEAN and China are top trading partners to each other since 2020 during the year of Covid pandemic.

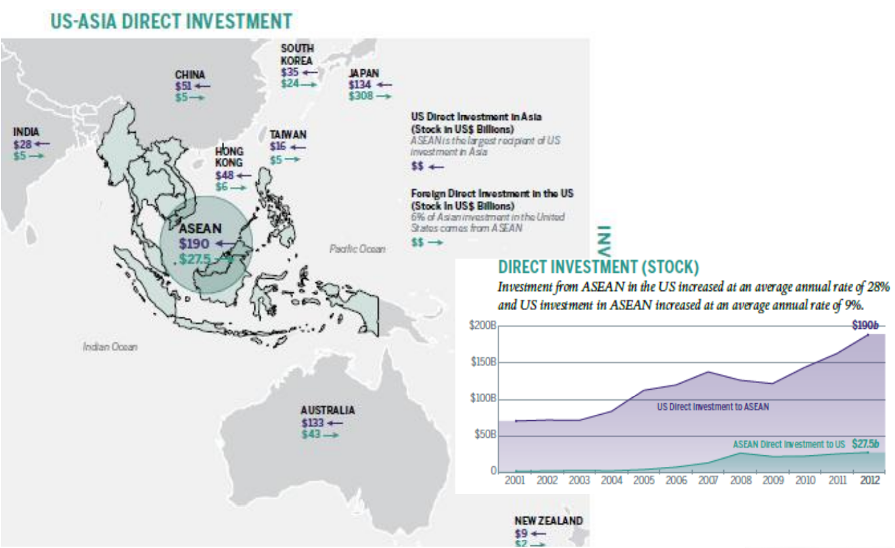

From the US perspective, South East Asia region is its largest investment in Asia of about $200b in ASEAN about 5 times and 4 times their investments in Japan and China respectively (see Figure 1).

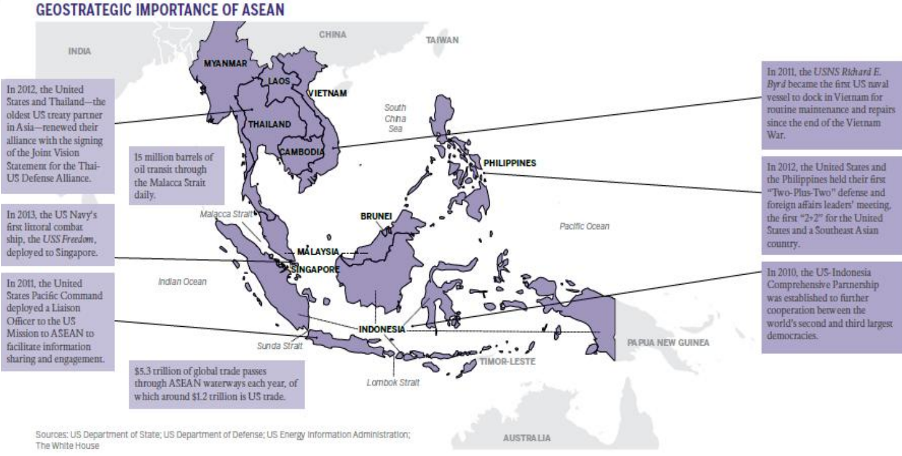

This is evident from US’s emphasis of ASEAN security with its various strategic collaborations with respective economies. For instance, in forging in 2010 the US-Indonesia Comprehensive Partnership which is a collaboration between 2nd and 3rd largest democratic economies, Philippines on “2+2 Defense” started in 2012, Joint Vision Statement with Thai-US Defense Alliance in 2012 (see Figure 2: GeoStrategic Importance of ASEAN).

In Asia, the US and its fellow members of the Quad alliance comprising of Australia, India and Japan had in March raised much global expectations in their aspiration for vaccine distribution leadership. The Quad’s leaders in unity, against China’s growing influence, announced to expand vaccine production by providing funding for India, the No 1 producer of vaccines globally, to manufacture up to 1 million doses for distribution to Asia, mainly Southeast Asia, by the end of 2023. But a surge of COVID-19 cases in India soon after saw Prime Minister Modi freezes vaccine exports to salvage its own situation.

As of May 2021, the Serum Institute of India which is the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer has not been able to fulfil production commitments of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine for Covax. In deferment, it states exports to the other countries later this year. Covax has only shipped out 68 million doses to developing nations so far, falling short of its target of 2 billion doses.

Concurrently, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced at a World Health Assembly meeting that China considered its COVID-19 vaccines to be a “global public good,” China has been exporting Sinopharm leading the international vaccine diplomacy. This diplomacy comes in a variety of donations, purchase or loans – an alternative offered primarily to the Latin American countries.

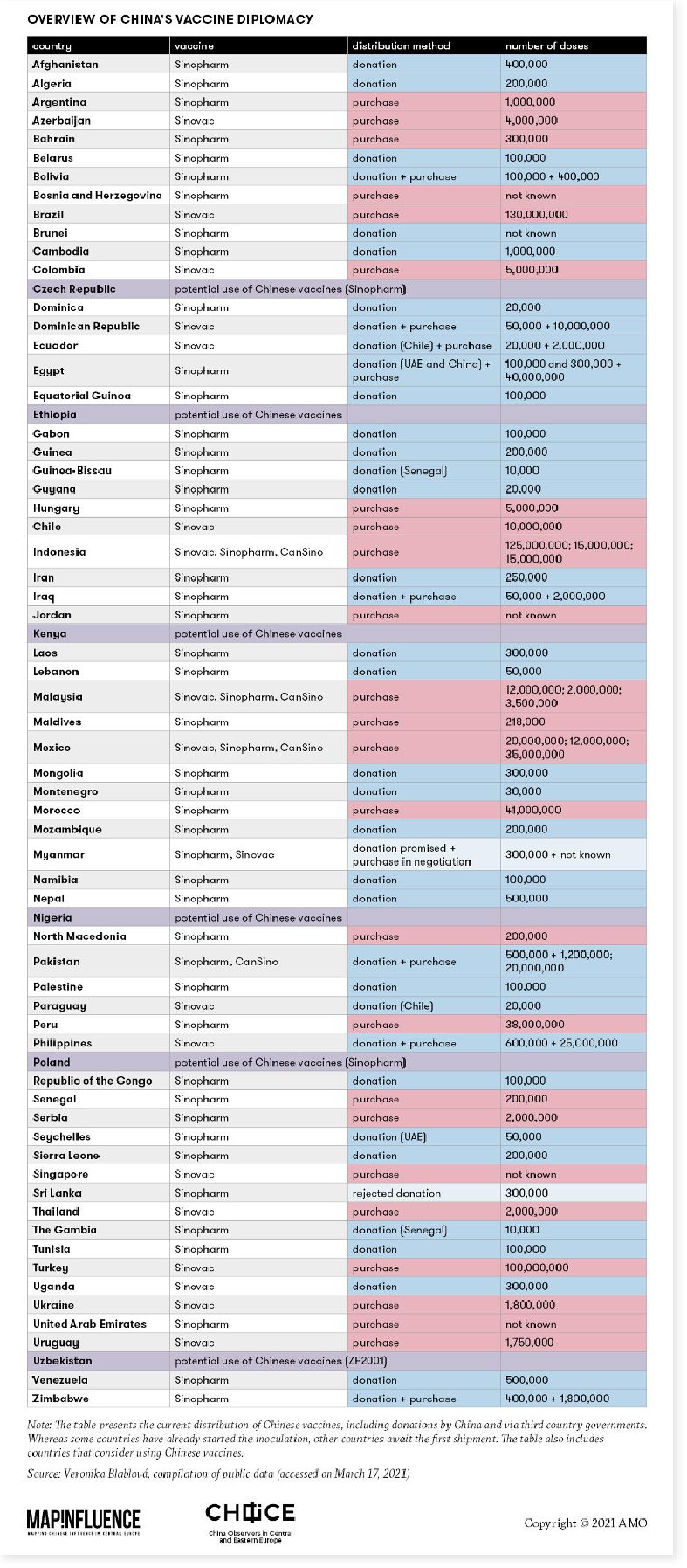

At that period, China has shipped about 265 million Covid vaccine doses, more than all other nations combined, with commitments to provide 440 million more, according to Airfinity. See Figure 3: Overview of China vaccine diplomacy on international distribution (Source: Veronika Blablova, compilations of various data).

In high-level diplomacy, China has affirmed its commitment to ASEAN with COVID-19 vaccine supply, masks and personal protective equipment since the pandemic. Fostering strong rapport, foreign ministers of China and the 10 ASEAN members have met in-person twice: first in Vientiane, Laos, 2020 to foster pandemic cooperation, and July 2021 in Chongqing marking the 30th anniversary of bilateral relations.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi frequents his visits across ASEAN cities and has hosted his regional counterparts warmly in China. Such frequent high-level exchanges marks the importance Beijing embraces as the region that became its largest trade partner in 2020.

In contrast, US official was slow to visit the region until the 7th month of Biden presidential inauguration when Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin and Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman visited this region. This is followed in August when Vice President Harris Kamala’s attempt to mount a charm offensive with a partnership vision, “Instead, our engagement is about advancing an optimistic vision that we have for our participation and partnership in this region,” she said.

The timing of the Harris’ visit coincided with the predicament of US’ hasty withdrawal from Afghanistan leaving Kabul in chaos. This created a crisis of confidence among US allies and partners. Harris has to reassure regional allies on the Afghanistan issue, raising the spectre of Vietnam war 40 years ago, is not a reflection of their future approach to South East Asia’s partners.

There was a need to re-establish new focal point of a Digital Silk-route to rival with China’s One-Road One-Belt policy. As Harris signed in Singapore a spectrum of digital agreement across cybersecurity, climate, epidemic intelligence sharing, and economic cooperation, as well as, the support she announced for Vietnam’s current COVID-19 outbreak.

Harris’ visit was viewed as an endeavour to fill the previous political vacuum left during the Trump’s administration.

China has been busy ensuring vaccine supplies to its ASEAN neighbors. With the exception of Vietnam, all ASEAN countries are on track to use Chinese vaccines. To Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, China promised vaccines in the form of a donation. The Philippines received a donation, which later resulted in Manila’s purchase of the vaccines, while Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand bought Chinese vaccines directly as their hybrid national inoculation exercise.

Southeast Asia is a key target for Chinese vaccine diplomacy, accounting for 29 per cent of China’s total vaccine donations and 25.6 per cent of its vaccine sales worldwide.

China’s vaccine outreach is helped by its first-mover advantage and consistent supplies when earlier the western countries were hoarding inventory for their national agenda. To live up to its promise of providing vaccines as a “global public good” and counteract suspicion that the country is engaging in self-serving “politics of generosity”, China should cooperate with Covex or WHO in accelerating the production and distribution of vaccines to the developing world.

Balancing China as a source of vaccine supplies, most Southeast Asian countries also diversify their vaccine portfolios. China’s exercise of soft influence through vaccine diplomacy has yet to generate essential trust mileages in Southeast Asia. This is comprehensible owing to Beijing’s past historical assertion of hard power in other areas, notably the South China Sea. As a consequence, China does not have a monopoly on vaccines in Southeast Asia.

But Sinopharm has been an essential vaccine source amongst the 9 ASEAN countries. Cost-effectiveness has been one of the key reasons to purchasing of China’s vaccines. While procurement details between countries are kept confidential China’s Sinovac is generally understood to be cheaper to buy and handle compared to mRNA-based vaccines.

In comparison, Indonesia was sold Sinovac at the price of US$13.60 per dose, while Pfizer and Moderna are estimated to cost around US$15-20 per shot.

Another challenge is the storage and transportation costs that the mRNA vaccines incur requiring a -70deg to -10deg environment, hence a stringer cold-chain capabilities in contrast to Sinovac’s 2-8deg storage temperature.

China’s manufacturing capabilities provided regular shipments of vaccines in consistent quantities which met around 58 per cent of the region’s orders to date. Cambodia has been receiving regular monthly shipments of Chinese shots (both donated and purchased) since February 2021. These regular deliveries have enabled Cambodia to inoculate 16.6 per cent of its population with at least one dose by early June 2021, making it the second fastest in the region behind Singapore of 81%.

America established its vaccine diplomacy as an opportunity to repair the damage to its leadership and show how democracies can deliver.

Concurrently, it aims to cast doubt on Beijing’s motives. US President Biden commented publicly, “Our vaccine donations don’t include pressure for favours or potential concessions. We’re doing this to save lives, to end this pandemic. That’s it. Period.”

This struck a chord with some countries who are apprehensive of China’s intention behind the perceived good will. Regional governments are wary with recent example with Australia having a Chinese trade reprisal for its perceivably anti-China policies. Some remember Singapore’s episode of having its military vehicles detained in Hong Kong as it made a statement on the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal’s judgment which Beijing perceived as “interfering in South China Sea issues”.

South-east Asia still has a relatively low vaccine coverage rate, with the exceptions of front runner Singapore and runner-up Cambodia. The region would welcome stocks of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna to boost its inoculation programmes, especially against the new variants.

Beijing distributes its hundreds of millions of vaccines directly to its recipient countries. Only 10 million are through Covax, the multilateral global procurement scheme which aims to distribute coronavirus vaccines equitably around the world.

In comparison, all but 20 million of America’s 580 million doses pledged so far will go through Covax.

There is efficiency to get Chinese vaccination which involves less bureacracy, but its recipients may also be more vulnerable to diplomatic pressure. From the research source of Bridge Consulting’s China COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker, China donated 22 million but sold 742 million. America has declare full donation to restore its humanitarian leadership rather than selling its vaccines.

While there are disparate South East Asia’s vaccines policies, most strive for independence without over-reliance on a single source.

Vietnam and Thailand strived for vaccines independence through aspiring home-grown vaccines undergoing clinical trials. Vietnam aims for technology licensing for mRNA vaccines production.

With the world’s 4th largest population, Indonesia took up China’s goodwill to host a regional vaccine production centre, while Pfizer’s partner BioNTech to build a biomedical production facility in Singapore by 2023.

Both US and China superpowers have promised to waive intellectual property protections of COVID-19 vaccines. However, waiving patents is not sufficient to boost vaccine manufacturing and supply globally and in South-east Asia.

As the economic competition has changed frontier towards a milder vaccination diplomacy amidst one of human’s darkest pandemic episode, America and China’s vaccine deliveries in South East Asia are appreciated. The endeavour to supply vaccines though competition is a helpful humanitarian endeavour.

If COVID-19 with its evolving variant is a new norm, helping more countries building capabilities to produce their own vaccines to save lives should prevail over political manoeuvre and diplomacy. Future will tell if this period will be marked the shining episode of positive international humanitarian collaboration or a dark rivalry of political manoeuvres.

Victor Tay

Governing Council and CEO of China ASEAN Business Alliance

CEO of Global Catalyst Advisory

MD of Stout Investment Banking

victor.tay@caba.org.sg

Victor is the Managing Director within the Investment Banking group and is based out of Stout’s Singapore office focusing on Southeast Asia. His areas of expertise include corporate strategic development, market entry and expansion strategy, direct investment, M&A and corporate finance advisory, and transaction support. Victor lectures at the Civil Service College International and speaks regularly to the regional media on various topics on future trends, business issues, innovation and technology, growth strategies, market expansion, and mergers and acquisitions.

1 Paya Lebar Link, #06-08

PLQ 2 Paya Lebar Quarter

Singapore 408533

secretariat@caba.org.sg

This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. Out of these cookies, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website. We also use third-party cookies that help us analyze and understand how you use this website. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with your consent. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies. But opting out of some of these cookies may have an effect on your browsing experience.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. Out of these cookies, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website. We also use third-party cookies that help us analyze and understand how you use this website. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with your consent. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies. But opting out of some of these cookies may have an effect on your browsing experience.

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. It is mandatory to procure user consent prior to running these cookies on your website.